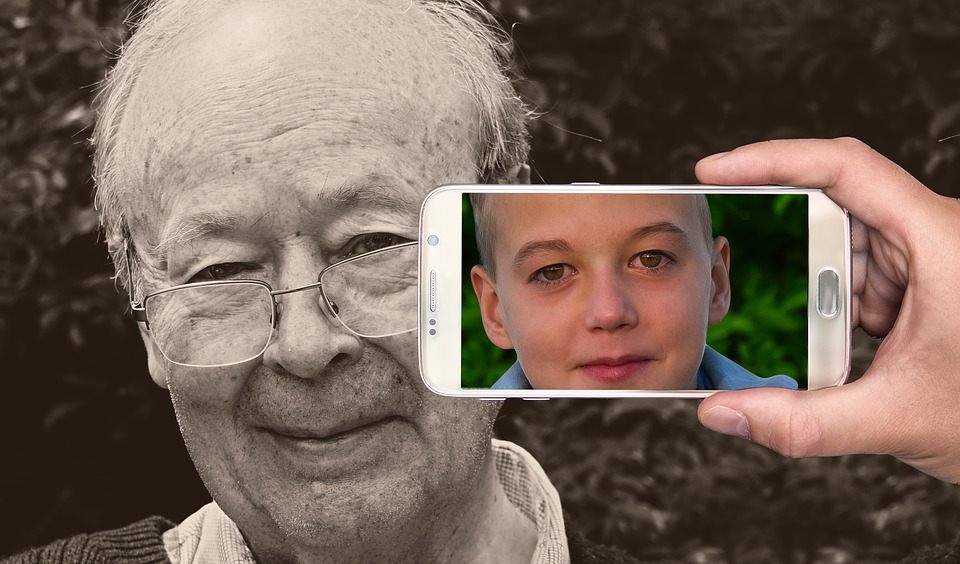

Chronologies for aging move, by clocks and calendars, from past to future across the lifespan. But not without exception. When it comes to social status for some individuals, time seems to reverse course. Teenagers demanding adult status complain relentlessly over being treated like a young child. We notice a helicoptering parent, babying a third grader with smothering overprotection. This phenomenon has been referred to, psychodynamically, as infantilization-treating an individual as if they were much younger than their chronological age. Earlier in my career, I became interested in the ways that adults with intellectual disability were infantilized, patronized, and robbed of their autonomy (Fettgather, 1987), including how they were given double-binding mixed messages to act like an adult even as they were treated like children (Fettgather, 1989). I am now turning to questions of how elders, especially those experiencing impairments associated with aging, may be diminished by practices associated with a similar social construct.

In recent years, I became acquainted with a legal device, “plenary guardianship”, wherein guardians retain all rights, powers and decisions over wards who are believed to lack capacity to care for themselves. This device seems to mirror the psychosocial experience of infantilization, but with potentially more devastating and permanent consequences. Based on a concept of parens patriae (parent of the nation) dating back centuries, the king had an explicit duty to protect those presumed to lack the capacity for managing their own lives-state sanctioned infantilization. Similarly, the contemporary “plenary guardian” is deemed ‘parent to the elder’ (or intellectually/psychosocially disabled person) who has been determined to lack adult capacity in a socio-legal construction of perpetual infancy-childhood. Plenary guardianship takes all decision-making from the ward and places it in the hands of an all powerful guardian.

In the spring of 2014, I attended the 3rd World Congress on Adult Guardianship. The conference highlighted worldwide, growing concerns and critiques of plenary guardianship. Many contemporary deconstructions of guardianship suggest that too often it is undue, overbroad and overprotective (Martinis, n.d., One Person, Many Choices; Blanck and Martinis, 2015). I argue that even benevolent guardianships may infantilize, fostering dependence and regression. And for elders of means, there is considerable anecdotal evidence of forced isolation with estate plundering by public and professional guardians. US Government Accounting Office Reports (GOA) beginning in 2004 (Government Accountability Office, 2004), and subsequent reports through 2012, show consistent patterns of financial exploitation and neglect. For example, one guardian embezzled $640,000 from the estate of an 87 year old man with Alzheimers Disease. Protective services discovered the man residing in a filthy basement and wearing just an old shirt and a diaper.

Beyond property, the very body of vulnerable elders becomes a commodity in an institution industrial complex that unites private business with government interests with an emphasis on profit making and social control (similar to the prison industrial complex). For example, Liat Ben-Moshe (Ben-Moshe, n.d., The Institution Yet to Come) emphasizes the nexus of impaired mind-bodies with an institution industrial complex dedicated to careerism: “political economists of disability argue that disability supports a whole industry of professionals that keeps the economy afloat, such as service providers, case managers, medical professionals, health care specialists etc”. With the absolute authority of a plenary guardianship, the concern is that guardians may force institutionalization into nursing home facilities where profit is the bottom line-a kind of pipeline into the institution industrial complex. Charlene Harrington, researcher at UCSF investigating care at nursing homes, summed up her findings, “Poor quality of care is endemic in many nursing homes, but we found that the most serious problems occur in the largest for-profit chains” that keep costs low to increase profits (Fernandez, 2011). A 2015 study at Hunter College also found that 12% of guardianships were initiated by nursing homes as a means to collect debt from residents (Bernstein, 2015).

With my colleague, Linda Kincaid, we have addressed elder rights to be free from plenary guardianships leading to chemical restraints (Fettgather and Kincaid, 2013) and forced isolation (Kincaid and Fettgather, 2014). Isolation is often achieved by limiting or denying visitation to hide poor living conditions or inadequate care from public scrutiny. Our current project, at the Coalition for Elder and Dependent Adult Rights, juxtaposes reports of guardianship abuse in GAO Reports and other sources with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). The project considers current problems in guardianship and institutionalization against criteria of the UNCRPD that seek to “promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedom by all persons with disabilities and to promote respect for their inherent dignity”. We contrast guardianship abuses with UNCRPD articles for equality, privacy, justice, liberty, and freedom from exploitation and torture. In particular, we place special emphasis on Article 12, equal recognition before the law. Article 12 says that “States Parties shall recognize that persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life.” Our concern is that plenary guardianship fails the standard of equal recognition before the law, and that alternatives must be vigorously pursued.

In that regard, we align ourselves with an international group of stakeholders who believe that incapacity should not be presumed (Dinerstein, 2012). Alternatively, we are committed to the presumption of capacity and to advancing supported decision-making as an alternative to plenary guardianship for elders and people with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities. In this model, decisions, supported by one or more persons, are made by the individual who has ultimate authority over his/her life. Personhood is honored, with no one acting as surrogate parent. We believe that this approach, with appropriate safeguards, oversight and subject to regular review, will disrupt the pipeline from guardianship to institution industrial complex. It will help reset clocks and calendars for heretofore infantilized adults and restore dignity, autonomy and adult status to the decision-making process.

References

Ben-Moshe, Liat. (n.d.) “The institution yet to come”: analyzing incarceration through a disability lens. Academia.edu, 1-16.

Bernstein, Nina (2015, January 25) To Collect Debt Nursing Homes Are Seizing Control Over Patients. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/26

Blanck, P. and Martinis, J. (2015). ‘‘The Right to Make Choices’’: The National Resource Center for Supported Decision-Making. INCLUSION, Vol. 3, No. 1, 24–33.

Dinerstein, Robert D.(2012) “Implementing Legal Capacity Under Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: The Difficult Road From Guardianship to Supported Decision-Making.” Human Rights Brief 19, No. 2, 8-12.

Fernandez, Elizabeth. (2011) Low Staffing and Poor Quality of Care at Nation’s For-Profit Nursing Homes. UCSF News Center. Retrieved from https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2011/11/11037

Fettgather, Robert (1989).‘Be an Adult’: A Hidden Curriculum in Life Skills Instruction for Retarded Students? Lifelong Learning: An Omnibus of Practice and Research, Vol 12, No.5, 4-5,10.

Fettgather, Robert (1987) The Relationship of Teacher Adult Ego State to Interactions with Retarded Students. Transactional Analysis Journal. Vol 17, No. 2, 35-37.

Fettgather, R. and Kincaid, L. (2013). Chemical Restraint in Long-term Care. Southern California Public Health Conference. Los Angeles, California

Government Accountability Office. (2004). Collaboration Needed to Protect Incapacitated Elderly People (GAO Publication No. 04-655:). Published: Jul 13, 2004. Publicly Released: Jul 22, 2004.Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office

Kincaid, L. and Fettgather, R. (2014) False Imprisonment and Isolation in Long-term Care. American Society on Aging Conference, San Diego, California

Martinis, J. G. (n.d.). One person, many choices: Using special education transition services to increase self-directionand decision-making and decrease overbroad or undue guardianship. Quality Trust for Individuals With Disabilities,1-29.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (n.d.)United Nations, 1-22. Retrieved from

3 comments

This is very important work and should be supported to develop and provide society with the means to address the reality of ageing populations and the consequent inevitable increase in a range of disabilities that include cognitive impairment.

As the authors indicate the ways in which we currently deal with this need are very much suboptimal and cross the ethical and moral line in many cases.

We need rigorous debate, based on well considered information and research, to guide the future course of societal responses to these emerging issues.

I was very interested in this article’s message. As a disabled individual I have the possibility of being subject to the abuse pointed out. One does not have to wait until their later years to be subject to “guardianship” if one were to suffer an aneurism or life changing accident you could easily find yourself subject to caretaker abuse.

Everyone is going to be faced with their aging body’s decline in health.

I live everyday on the razor’s edge of getting good vs horrible physical and emotional care because I am totally disabled. (No use of my arms or legs and legally blind).

Unfortunately I’ve had more then one bad caregiver experience in my life where I was physically, financially and emotionally abused.

This topic should be at the forefront of discussion due to the aging population as well as the number of disabled individuals being born

I read this article with great interest. The author points out an alarming situation that affects our most vulnerable populations, the disabled and elderly. Readers who feel they need not worry must not realize that they can become disabled suddenly and without warning, and they will almost certainly become elderly. We are all at risk for abuse and extortion by “guardians.” Modern societies generally apply more severe punishments to those who commit crimes “under the color of law,” because neglect or abuse of vulnerable individuals under one’s care is morally repugnant. Such acts occur too often in the nation’s legal-industrial complex of guardianship/conservatorship. Independent monitors, audits, and inspections are desperately needed to protect our disabled and elderly. Like Cassandra, this author has given us advance notice. It is now our obligation to call for investigations and reform.