Note: The authors originally prepared this piece as a policy brief for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission and the section on Aging.

Grumpy, frail, sick. Stereotypes of aging are pervasive in the American mindset. The media, use of language, and culture facilitate negative images of aging and often depict older adults as cantankerous elderly with illness or need for care [1]. These images can have profound consequences on the lives of older adults.

Why do words matter?

Ageism is the specific use of negative language and derogatory images to discriminate against a certain population group [2]. The words we use are the essence of our communicative exchanges and shape the perceptions and meanings of the things and people around us [3]. These perceptions are further compounded by the images we use to give life to those words. For instance, an image of a grumpy man with a walking cane symbolizes an elderly man with a disability. These images become part of our social constructs of aging. After repetitive use in movies, television, stories, and advertisements, these images become socially accepted. Further, the images influence and shape our interactions, our consumer choices, and our political views. They shape our norms, our attitudes, and our culture [4].

A Model to Examine Ageism in Aging Policy-making

Symbols of aging as sick and frail depict growing old as an unpleasant process. They may conjure ideas among the young that older people are physically frail and a burden from both a monetary and time perspective, as well as foster a narrative of ‘dependency’. Policy responses that are developed from a ‘dependency’ perspective may thus create barriers to thinking about alternative narratives such as those of capability or independence, whereby older adults are viewed as active participants in their communities, or narratives that optimize improving social and mental health [5], [6].

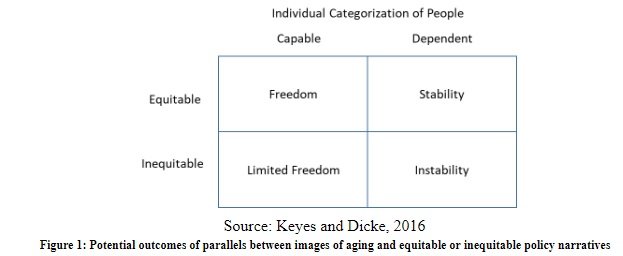

Humans tend to categorize people based on their membership in a group [7]. Decisions on selecting the categories in which people are placed is influenced by the socially constructed beliefs held by society. Images of aging that have perpetuated across time tend to categorize older adults as either dependent or capable [8]. These beliefs have the power to shape the policy responses of public officials toward citizens that result in equitable or inequitable outcomes [9]. As outlined in our recent work, evidence suggests that the potential policy outcomes for older adults whether capable or dependent are matched with equitable and inequitable policies affecting: Freedom, Stability, Limited Freedom, or Instability [10].

Figure 1 provides a 2 by 2 model to consider relationships between images of aging and resulting policy outcomes under these four conditions:

Figure 1 provides a 2 by 2 model to consider relationships between images of aging and resulting policy outcomes under these four conditions:

- Freedom: Older adults experience little public interference; individuals have access to private resources; public policies allow individuals to optimize choices

- Stability: Older adults have access to some government resources to subsidize their living environment

- Limited Freedom: Not all older adults live in communities with housing options and price points available to them

- Instability: Older adults dependent on government support have few or no housing options and unequal living arrangements; for instance, they may not have any Medicaid nursing home options in their local community.

Research also finds that today’s images of aging emerged through an evolution from the late 1800s to the present time from growing generational tensions, encouraged retirement, a rise of poverty among older adults, and increased longevity [11]. An examination of federal policy responses also suggest a parallel between negative images of aging and dependency policy narratives that ultimately ignore the capacity and contribution of older adults [12]. Recent policy narratives have attempted to break through negative images of aging with a focus on health and independence in older age. Our 2 by 2 model provides a lens that can be used to examine values against policy decisions.

Impact on the Lives of Older Adults

As supported by our findings presented above, ageism has direct implications on the lives of older adults. The influence of negative stereotypes may perpetuate in the following areas and result in inappropriate behavior.

- Family Life – Attitudes that older adults are a financial burden to family members; feelings of being demoralized, and marginalized or patronized [13]

- Ongoing Employment – Encounters of difficulty in hiring and maintaining employment, experiencing job displacement [14], and the lack of job promotion [15]; and views that older adults are unwilling to change their behaviors or ideas [16]. By 2024, 13 million individuals over the age of 65 will make up the national workforce [17].

- Health Care – Limitations in available physician services relative to lack of interest and difficulty in treating complex health conditions [18], avoidance by physicians due to complexities with Medicare [19]; and overall devaluation of concerns [20].

- Public policy – Sentiment that older adults are a social burden [21].

Recommendations

Policy makers are encouraged to:

- Understand how images shape their own views and beliefs

- Consider the evidence used to make policy decisions

- Consider their duty to safeguard the individual rights of all individuals, including older Americans

Making strides to break down negative images of aging requires attention to our own perceptions and use of language.

Policy makers can:

- Influence the way older adults are portrayed in the media

- Can recognize older adults in their workforce

- Prompt pro-active behavior to ensure equitable policy outcomes

Efficient public policy and administration requires public officials to understand the changing demographics in the communities they serve. They should also be aware of the cultural biases in their societies and how these may affect policy outcomes. This is critical as many communities throughout the nation are already experiencing a doubling of their older adult population. Public officials will need to think strategically on how to support a growing older adult population with limited public resources. Cultural competency suggests that public officials explore and understand the needs of diverse groups of people and self-evaluate their individual values and judgments relative to serving a culturally diverse community [22],[23]. Attention to cultural competency means that public officials cannot ignore the powerful persuasion of images as they enact policies affecting the lives of older adults.

Resources

Leading Age, Ageism Resources, http://www.leadingage.org/ageism-resources-0

Brock, Susan, The Legacy Project, http://www.legacyproject.org/guides/ageism.html

Robin, Laurens, The Pernicious Problem of Ageism, Aging Society of America, http://www.asaging.org/blog/pernicious-problem-ageism

Barrington, Linda, Ageism and Bias in the American Workplace, Aging Society of America, http://www.asaging.org/blog/ageism-and-bias-american-workplace

AARP, Age Discrimination Fact Sheet, https://www.aarp.org/work/employee-rights/info-02-2009/age_discrimination_fact_sheet.html

References

- Dail, P. W. (1988). Prime-time television portrayals of older adults in the context of family life.The Gerontologist, 28(5), 700–706. doi:10.1093/geront/28.5.700

- Palmore, E. B. (2001). The ageism survey: First findings/response.The Gerontologist, 41, 572–575.

- Miller, H. T. (2012).Governing narratives. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

- Morgan, G. (2006).Images of organization. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Knickman, J. R., & Snell, E. K. (2002). The 2030 problem: Caring for aging baby boomers.Health Services Research,37(4), 849–884. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.56.x

- Naaldenberg, J.,Vaandrager, L., Koelen, M., & Leeuwis, C. (2012). Aging populations’ everyday life perspectives on healthy aging: New insights for policy and strategies at the local level. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 31(6), 711–733. doi:10.1177/0733464810397703

- Pinker, S. (1999). How the mind works.Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 882(1), 119–127. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08538.x

- Keyes, L., &Dicke, L. (2016). Aging in America: A parallel between popular images of aging and public policy narratives. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 38(2), 115-136.

- Alkadry, M. G. (2003). Deliberative discourse between citizens and administrators if citizens talk, will administratorslisten? Administration & Society, 35(2), 184–209.

- Keyes andDicke. (2016)

- Keyes andDicke. (2016)

- Thornton, J. E. (2002). Myths of aging or ageist stereotypes.Educational Gerontology, 28(4), 301–312. doi:10.1080/036012702753590415

- Nussbaum, J. F., Pitts, M. J., Huber, F. N., Krieger, J. L. R., &Ohs, J. E. (2005). Ageism and ageist language across the life span: Intimate relationships and Non‐intimate interactions. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 287-305.

- McMullin, J. A., & Marshall, V. W. (2001). Ageism, age relations, and garment industry work in Montreal. The Gerontologist, 41(1), 111-122.

- Cardinali, R., & Gordon, Z. (2002). Ageism: No longer the equal opportunity stepchild.Equal Opportunities International, 21, 58–68.

- Shea, G. (1991).Managing older employees. Oxford, UK:Jossey-Bass.

- Toossi, M,Torpey, E. (2017). Older Workers Labor Force Trends and Career Options, Bureau of Labor and Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2017/article/older-workers.htm, retrieved December 20, 2017.

- Damiano, P.,Momany, E., Willard, J., & Jogerst, G. (1997). Factors affecting primary care physician participation in Medicare. Medical Care, 35, 1008–1019.

- Adams, W. L., McIlvain, H. E., Lacy, N. L.,Magsi, H., Crabtree, B. F.,Yenny, S. K., & Sitorius, M.. (2002). Primary care for elderly people: Why do doctors find it so hard? The Gerontologist, 42, 835–842.

- Nussbaum et al.(2005)

- Palmore. (2002)

- Rubaii, Nadia and CrystalCalarusse. (2012). “Cultural Competency as a Standard for Accreditation.” In Cultural Competency for Public Administrators, edited by Kristen A. Norman-Major and Susan T. Gooden, 219-243. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Rice, Mitchell F.(2007). “Promoting Cultural Competency in Public Administration and Public Service Delivery: Utilizing Self-Assessment Tools and Performance Measures.”Journal of Public Affairs Education: 41-57.